|

科学哲学ニューズレター |

![]()

No. 53, January 16, 2004

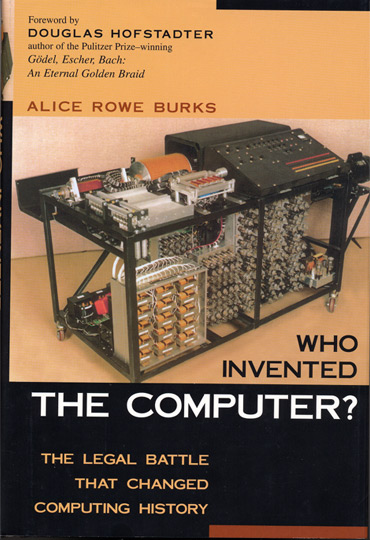

Book Review by S. Uchii: Alice Row Burks, Who Invented the Computer? The legal battle that changed computing history, Prometheus Books, 2003.

Editor: Soshichi Uchii

1. WHO IS ALICE BURKS?

Douglas Hofstadter, the renowned author of Goedel, Escher, Bach, in the Foreword of Burks's book, writes as follows:

What we have in Who Invented the Computer? is a classic battle between a little-known underdog and a massively backed "easy winner". Alice Burks has taken on formidable opponents, but she has done a formidable job of building and defending her case. You, the readers of this book, are now the jury. (p. 14)Indeed, this is an impressive book, covering the wide range of early computers: Atanasoff's ABC, ENIAC at Moore School, and EDVAC; it also covers secondary materials with respect to the controversy on the ENIAC trial and the priority of inventing electronic digital computer.

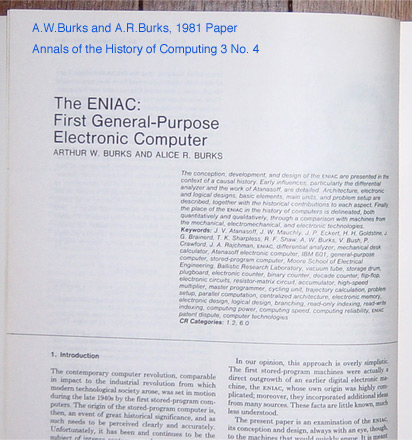

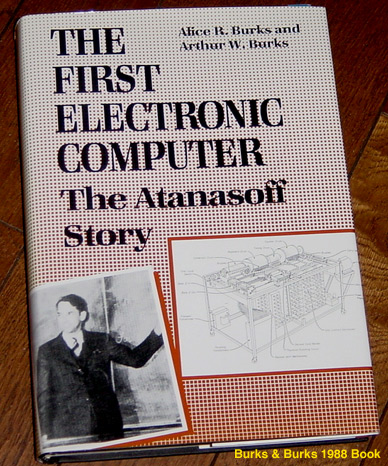

But who is Alice Burks? She is the wife of Arthur W. Burks, the reviewer's mentor and one of the members of the ENIAC team at Moore School, University of Pennsilvania; he is now the only survivor of the team. As you may well know, ENIAC is usually referred to as the "first electronic computer" in most popular descriptions of the history of computers. And Alice herself has a close connection with ENIAC, because she was one of the "computers" at Moore School, for preparing firing tables for field use, when the ENIAC project began. Arthur and Alice collaborated for their monumental 1981 paper on ENIAC; then for the 1988 book on Atanasoff Computer (now called ABC Machine). Thus Alice became an expert of the early history of digital computers. As you read the book, you will realize her expertise is extraordinary; she accuses most historians of computer for not examining relevant documents, the most important of which are the ENIAC trial records.

2. ENIAC TRIAL

For the readers unfamiliar with the ENIAC trial, let me first extract relevant passages from the book (also see Newsletter 4, where I reviewed the Japanese translation of Mollenhoff 1988).

Although the University of Pennsylvania had unveiled the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) in 1946, the patent was not issued until 1964. In the meantime patentees J. Presper Eckert and John W. Mauchly had sold their rights ---and their company---to Remington Rand, and Remington Rand had merged with Sperry Gyroscope to form Sperry Rand.

Now Sperry Rand, ENIAC patent in hand, was demanding huge royalties on all the electronic data processing sales of all its large competitors, except IBM and Bell telephone Laboratories, with whom it had signed cross-licensing agreements. And Honeywell, one of those competitors, was challenging the patent's validity, claiming derivation from John V. Atanasoff, among other charges. (p. 23)

The trial took place in Minneapolis, and District Judge Earl R. Larson presided (the trial had run from June 1971 to March 1972, and Larson's decision was issued on October 19, 1973). Although many historians and critics argue that this decision contains contradictions and based on ignorance on technical matters, Alice Burks consistently argues that the decision is consistent, tightly organized, and well-founded on solid evidence; she argues, in addition, these critics either misunderstood the decision, or they did not carefully read the decision (still less went through the trial transcript) which is quite carefully prepared by Larson.

In the trial, both Atanasoff and Mauchly took the witness stand, the former for Honeywell, the latter for Sperry Rand. There are many interesting things to say about their performance, but we will skip them. Instead, we will go directly to the heart of Larson's decision.

3. LARSON'S DECISION

Since we are going to read the decision for the ENIAC trial, it is important to notice Sperry Rand's and Honeywell's positions at issue in this trial. Sperry Rand is claiming invention of the "automatic electronic digital computer" and thereby claiming royalties from all competitors producing any such computer. ENIAC patent was not meant for the "general purpose" automatic electronic computer. Thus, Larson's decision in this regard (Finding 1) points out that Honeywell does not have to attack specific claims as regards the content of the invention; and whether ENIAC is "derived" from any prior machine, is also to be judged in the same terms. If you miss this point, it may become harder to understand the decision. Thus comes Larson's Finding 3:

3.1 The subject matter of one or more claims of the ENIAC was derived from Atanasoff, and the invention claimed in the ENIAC was derived from Atanasoff.

3.1.1 SR [Sperry Rand] and ISD [Illinois Scientific Developments, SR's subsidiary] are bound by their representation in support of the counterclaim herein that the invention claimed in the ENIAC patent is broadly "the invention of the Automatiiic Electronic Digital Computer".

3.1.2 Eckert and Mauchly did not themselves first invent the automatic electronic digital computer, but instead derived that subject matter from one Dr. John Vincent Atanasoff. (Quoted from Burks, p. 146)

Then follows a series of statements as regards: how Atanasoff developed ABC machine, how Mauchly met Atanasoff and knew ABC machine, and how Mauchly applied the "subject matter" to the construction of ENIAC. The Court found the testimony of Atanasoff credible. And because of this "derivation", Larson ruled the ENIAC patent invalid. It must be noticed that the decision is based on all of the documents and devices submitted by both sides, as well as many other testimonies and cross examinations. Thus, Alice Burks argues that historians should not disregard this decision, even for their "scholarly" works. If they want to depict a different version of the history of computing, they should present their own evidence, as solid as those presented in the trial.

Larson's decision contains many other things. Burks now goes on to Finding 4, titled "Inventors". In this, Larson declared Mauchly and Eckert "the inventors" of the ENIAC, "the true and actual inventors" as named in their patent.

This section has been cited by critics as evidence of flawed reasoning on the part of the judge because, it is argued, it contradicts the preceding finding that the ENIAC was derived from Atanasoff. How, the argument goes, could Mauchly and Eckert be "the inventors" if their invention was derived from a prior inventor?

The answer is that this finding was not addressing the issue of prior inventors but of coinventors on the ENIAC team, and Larson was merely responding to a Honeywell charge that Eckert and Mauchly wrongfully omitted the names of other Moore School inventors from the ENIAC patent. (p. 150)

Although Larson admitted contributions by those "other members of the Moore School team" (including Arthur Burks), he ruled that their petition of "coinvention" is now too late for consideration (pp. 237-8), and the ENIAC patent was already declared invalid anyway.

In view of this consistent reading, I completely agree with Burks' contention. Many people, including scholars of some eminence, tend to give in to the temptation of an easy attribution of "contradiction" to their opponents; I myself have such experiences of being charged of "inconsistency", despite my clear arguments and expressions.

It should be noted, in passing, that Larson found several other grounds (whihch have nothing to do with "derivation") for declaring the ENIAC patent invalid. These are concerned with the premature disclosure of the computer (public use, placement on sale, and publication of its key features; see pp. 151-159), prior to the application for a patent. But we will skip these, except for the most important one: the "publication" of von Neumann's "First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC" (June 1945).

4. WHY IS VON NEUMANN'S DRAFT RELEVANT TO THE ENIAC PATENT?

As some readers may know, von Neumann's "First Draft" caused great bitterness, especially for Mauchly and Eckert ( I briefly touched on this problem---not in any depth--- in my recent book, Ethics of Science, p. 6). First, let us see how this "publication" happened.

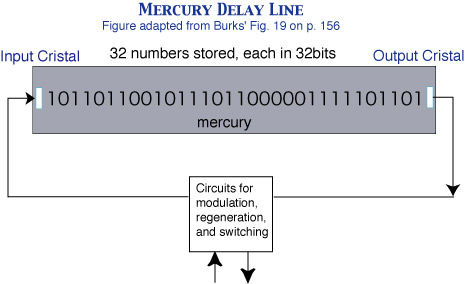

The report in question had followed a series of meetings at the Moore School that spring [1945], called to discuss the computer that would succeed the ENIAC. The major improvements of the EDVAC over the ENIAC anticipated at that time was the move away from counters, which, as they computed, also stored the latest results. Now there would be two distinct units: first, a regeneraqtive main store based on Eckert's concept of a mercury-delay-line memory; second, a binary serial adder separate from but interacting with that memory. (p. 155)

Here, the key invention was Eckert's mercury-delay-line (see the simplified and diagramatic figure, for the device used for EDVAC), which enabled a large and erasable memory, and moreover made possible a faster computation (ten-times faster than the ENIAC). "Regeneration" means that data are periodically refreshed, because otherwise they would be weakened and lost; this process was vital already in ABC machine (it was first invented there). Now, what is most important here is that Eckert's mercury-delay-line made possible the "stored program" computer. As regards this notion, Burks has many things to say, and we will come back to this later. Right now, we are concerned with the relevance of this draft to the ENIAC patent.

Participants in the four March and April 1945 meetings were Eckert, Mauchly, Burks, Goldstine ..., S. Reid Warren ..., and John von Neumann .... Von Neumann's "First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC" resulted from his offer, at the end of the second meeting, to summarize and organize the discussions. The offer had been received enthusiastically, but in fact his report both fell short of summarizing the discussions and went well beyond their subject matter. (p. 157)And what is crucial is the date of its publication, and the date of the filing of the ENIAC patent:

The filing date for the ENIAC patent was june 26, 1947, so that its so-called critical date was June 26, 1946. That is, any public disclosure prior to June 26, 1946, would render the patent invalid. (p. 152)Moreover, Larson found many features of the ENIAC patent described in the "First Draft".

As to the report's applicability to the ENIAC patent, Larson ruled that it included certain features of the ENIAC, even though it did not address those features as such; that, indeed, it anticipated nine particular claims in the ENIAC patent. The judge's finding that this publication was an "enabling disclosure" of the ENIAC rests upon these ENIAC features and ENIAC patent claims. ...

Just as seriously, Judge Larson ruled that the computer described in the von Neumann report was an "automatic electronic digital computer"! So here again was the issue of that entity, which the Sperry side had chosen to designate "the claimed subject matter" of the ENIAC patent. This Sperry strategy misfired in the matter of priority of invention, as Atanasoff's earlier invention was found to be such a computer. And now it misfired in the matter of prior publication, as the von Neumann report was found to disclose such a computer before the critical date. (pp. 157-8)

5. MAUCHLY-ECKERT VS. VON NEUMANN OVER THE PRIORITY ON EDVAC

In this connection, Alice Burks also contributes greatly to clarifying the priority problem with the EDVAC. As is well known, von Neumann has been acknowledged as the main advocate of the "stored program" computer in pupular journalism, because of his "First Draft". Eckert, on the other hand, angrily accuses von Neumann for writing and distributing "First Draft" without acknowledging the contributions of Moore School team, especially of Eckert. Burks points out, however, that the stored-program concept had a twofold development: the first part, Eckert's; the second, von Neumann's (p. 160).

In brief, von Neumann had depended upon Eckert's advances over the ENIAC to move on to his own equally ingenious concept. As we saw, on Eckert's conception the speed of computation would be markedly enhanced, both by the combination of a large, fast regenerative memory with an electronic serial adder and by the much faster entry of arithmetic data, and especially of coded instructions, at the start of a given problem. ...

What von Neumann did was take further advantage of the erasable feature of the merucury-delay-line memory, which Eckert had seen as allowing for easy replacement of an old program by a new one at the end of one problem run and the start of the next. Von Neumann saw that such a feature would not only expediate entry of a preset program as in the case of the ENIAC, but would also allow that program to change automatically as the problem ran. (p. 160)

This was one of the features of "First Draft" where von Neumann went well beyond the discussion at Moore School. Another feature was the proposal of a cathode-ray-tube (now familiar as CRT, in TV and computer display) as an alternative memory device. This "would allow random access of data and instructions, a great architectural improvement over the serial access of the delay-line tubes and one that became standard for main memories" (p. 161). As a matter of fact, mercury- delay-line memory was used in EDVAC, UNIVAC (a product of Mauchly and Eckert), and EDSAC (made by Maurice Wilks at Cambridge), whereas CRT was used in IAS computer made by von Neumann's group at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton.

In any case, ill feelings on both side erupted in March 1946. Mauchly and Eckert were indignant over the "First Draft", whereas von Neumann suspected Mauchly and Eckert were trying to steal---to patent---his ideas; von Neumann told Arthur Burks not to tell them about the IAS computer being planned for the Institute (p. 162). However, what is valuable in Alice Burks' books is not how the quarrel developed between them, but her scholarly analysis of the "Minutes of 1947 Patent Conference, Moore School of Engineering, University of Pennsylvania", which was reproduced in a1985 issue of Annals of the History of Computing. Judge Larson also referred to the original, in his decision on the ENIAC patent. The three major figures, together with other persons representing Moore School and Army Ordnance, met again in order to discuss the patentability of EDVAC, and their own due contributions to EDVAC. Although I will refrain from getting into detail, the upshot is quite interesting.

They [Mauchly and Eckert] applied for patents through their own attorneys, not revealing any information to von Neumann. And, ..., they were granted a patent not just on the mercury-delay-line memory but also on the broad concept of a regenerative memory. They obtained various adder patents, as well. Then, years later, Judge Larson found the Regenerative Memory patent unenforceable because of derivation from Atanasoff, and the adder patents, also really derived from Atanasoff, unenforceable on other, equally serious, grounds. (p. 293)Thus, the ENIAC trial had relevance even to the newer machine EDVAC and related problems. Alice Burks states her own evaluation (say, from an ethical point of view) on the both sides of EDVAC controversy succinctly:

VN [von Neumann] , though expressly uninterested in personal monetary gain, has two top concerns. One is that he be credited with his ideas; the other is that new ideas be spread, in order, as the judge puts it, "to advance the state of the art." This latter, however, does not excuse the distribution of the ideas of others, together with one's own, without their permission, particularly as it is done with no indication that essential ideas emanated from those others.

E and M [Eckert and Mauchly], for their part, are so interested in monetary gain, as well as credit, that they are willing not just to claim but to patent the ideas of others along with their own. After they leave the Moore School in 1946 to go into business, they take out patents on ideas for the EDVAC that originated with A [Atanasoff]! Indeed, they patent the heart of A's invention: his idea for binary serial adders and both his idea for and his form of regenerative memory. (p. 382)

One of the recurring themes in her book is that too many historians just ignore the ethical issue of priority, of patent. This especially applies to Nancy Stern (one of the major advocates for Mauchly-Eckert cause; see pp. 211-220, especially p. 217). I have made a similar comment on McCartney's recent book, in my book (Uchii 2002, p. 5).

6. AS REGARDS REDEFINITIONS OF "COMPUTER"

This review is already getting too long, but I wish to touch on the last issue which may be quite instructive to historians. Alice Burks mentions four major obstacles to resolving the dispute over invention of the electronic computer: (1) misconstruing of the dispute itself (e.g., by failing to ditinguish "automatic electronic digital computer" and "general purpose computer"), (2) a challenge to the fact of "derivation" on various misunderstandings and fabrications about the history, (3) denying Atanasoff's accomplishments, and (4) a redefinition of the word "computer" that excludes the ABC machine (pp. 247-265). We will now touch on (4).

After citing various attempts at redefining "computer", Burks argues as follows:

A readily apparent objection to these attempts to define critical terms on the basis of "current" usage is that "current" is constantly changing. But the chief objection that Art and I have is that such definitions miss the opportunity to present the history of the modern computer as an evolving process. Historians of science do not ordinarily deny invention to the pioneers on the basis of later advances, but cite the succession of advances from the very first "light bulb" of inspiration that culminated in its reduction to practice, at however rudimentary a level. (p. 266, the reviewer's italics)Although I am not a historian of science but a philosopher of science, I think this view is sound; for history is not a simple application of definitions, such as "who satisfied which definition". What counts is "who invented or discovered what", basically a factual question, although "what" does depend on definitions in one way or another; but these definitions are similar to a definition of species in evolutionary biology---by no means clear-cut, and we have to take lineage into consideration. Thus Burks concludes:

Finally, I would just note that at a basic level no definition--or redefiniton---of terms should affect either the issue of priority of invention or that of derivation of an invention from an earlier invention, so long as original and enduring principles are entailed. To exclude Atanasoff's computer from consideration on the basis of definition, especially in the matter of priority, seems to me inappropriate, given the list of "firsts" the ABC encompassed, "firsts" that persist in the most sophisticated computers to this day. (pp. 267-8)I have mostly skipped those interesting parts which tell Art and Alice Burks's personal struggles for publishing and defending a "new and heretic view", from 1981 to the present. If I may add a word on these, it seems that it is their strong belief in a true representation of history based on solid evidence, that supported their consistent and persistent activities. And, it should be noticed that at the personal level, they were deeply impressed by the integrity of Atanasoff (see, e.g., pp. 410-412). Their descriptions of Mauchly and Eckert may look like a sort of "defamation" (Kathleen Mauchly's expression), but that is because their descriptions are made on the same standard as that is applied to Atanasoff; a sharp contrast is made not because of the manner of Burks's presentation but because of Mauchly's and Eckert's own words and deeds, I would say. Alice Burks' book is a "must" for any historians of computer.

REFERENCES

Burks, A.W., and Burks, A.R. (1981) "The ENIAC: First General Purpose Electronic Computer", Annals of the History of Computing 3, No. 4, 310-389.

Burks, A.R., and Burks, A.W. (1988) The First Electronic Computer: The Atanasoff Story, The University of Michigan Press.

Mackintosh, A.R. (1988) "Dr. Atanasoff's Computer", Scientific American 259, No. 2, 90-96.

McCartney, S. (1999) ENIAC: The Triumphs and Tragedies of the World's First Computer, Walker and Company.

Mollenhoff, C.R. (1988) Atanasoff: Forgotten Father of the Computer, Iowa State University Press.

Uchii, S. (2002) The Ethics of Science [in Japanese], Maruzen.

See also Atanasoff Archive at Iowa State University, where you can see the original of Larson's "Finding 3".

Last modified Dec. 1, 2008. (c) Soshichi Uchii