![]()

Eddington on 1919 Expeditions

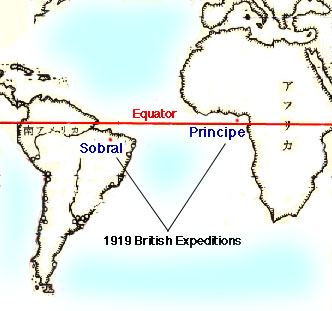

Royal Society and Royal Astronomical Society sent two teams, to Sobral and to Principe.

Eddington on 1919 Expeditions

In chapter 7 of his book, Space, Time and Gravitation, Sir Arthur Eddington reports the British Expeditions to Sobral (Brazil) and Principe (West Africa), for checking one of Einstein's predictions from his general relativity, as follows:

In a superstitious age a natural philosopher wishing to perform an important experiment would consult an astrologer to ascertain an auspicious moment for the trial. With better reason, an astronomer to-day consulting the stars would announce that the most favourable day of the year for weighing light is May 29. The reason is that the sun in its annual journey round the ecliptic goes tyhrough fields of stars of varying richness, but on May 29 it is in the midst of a quite exceptional patch of bright stars---part of the Hyades---by far the best star-field encountered. ... by strange good fortune an eclipse did happen on May 29, 1919. (113)

Eddington himself went to Principe.

The observers had rather more than a month on the island to make their preparations. On the day of the eclipse the weather was unfavourable. When totality began the dark disc of the moon surrounded by the corona was visible through cloud, ...

Sixteen photographs were obtained, with exposures ranging from 2 to 20 seconds. The earlier photographs showed no stars, ...; but apparently the cloud lightened somewhat towards the end of totality, and a few images appeared on the later plates. ... one plate was found showing fairly good images of five stars, which were suitable for a determination. This was measured on the spot a few days after the eclipse in a micrometric measuring-machine. The problem was to determine how the apparent positions of the stars, affected by the sun's gravitational field, compared with the normal positions on a photographs for comparison had been taken with the same telescope in England in January. The eclipse photograph and a comparison photograph were placed film to film in the measuring-machine so that corresponding images fell close together, and the small distances were measured in two rectangular directions. From these the relative displacements of the stars could be ascertained.

The results from this plate gave a definite displacement, in good accordance with Einstein's theory and disagreeing with the Newtonian prediction. ...

It was not until after the return to England that any further confirmation was forthcoming. Four plates were brought home undeveloped, as they were of a brand which would not stand development in the hot climate. One of these was found to show sufficient stars; and on measurement it also showed the deflection predicted by Einstein, confirming the other plate. (114-116)

Now, you may wonder: why does such evidence (measurement on photographs) provide confirmation of Einstein's prediction? Eddington does provide reasons for this in the rest of this chapter, and Deborah Mayo also gives a detailed analysis of this reasoning, in 8.6 of her Error and the Growth of Experimental Knowledge (pp. 278-293). See the following figure, adapted from Mayo's Figure 8.2, which gives misleading displacements!

In 1922, another observation was made at Wallal, Western Australia, and W. W. Campbell and R. J. Trumpler determined the deflections of the 15 stars as in the following figure (figure from Misner et al, Gravitation, Freeman and Co., 1973, 1104).

For more recent confirmation of this kind (quasar light deflection), see Stachel's "History of Relativity" in Twentieth Century Physics, vol. 1 (1995), 305-306 (Japanese translation, 1999, 313-315) .

Last modified Jan. 26, 2003. (c) Soshichi Uchii