Newton on the God's Intervention

From his Letters to Richard Bentley (1692-3)

Clarke's insistence on the "mere will of God" seems to be shared by Newton himself. This is clearly and dramatically shown in his letters to Richard Bentley, written from 1692 to 1693; these letters are very interesting in that they show Newton's cosmology, as it were. Unlike Leibniz who wishes to start from metaphysical principles, Newton's considerations seem to be primarily based on empirical phenomena to be explained, and he invokes God's intervention if he comes to the point where he can find no explanation. He says, however, that this shows his own investigation of nature is conducive to strengthening the belief in God.

Richard Bentley (1662-1742) delievered the first series of Boyle lectures in 1692, and before publishing these lectures (titled "A Confutation of Atheism") he asked Newton on several points, whether Bentley's ideas are right, in conformity with Newton's ideas. (Figures supplied by S. Uchii)

When I wrote my treatise about our System I had an eye upon such Principles as might work with considering men for the belief of a Deity and nothing can rejoyce me more than to find it useful for that purpose. ... (Correspondence, 233)

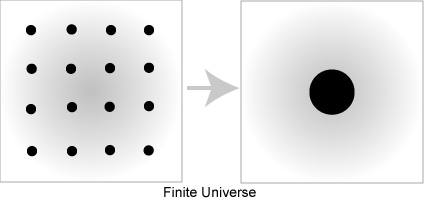

As to your first Querry, it seems to me, that if the matter of our Sun and Planets and all the matter in the Universe was evenly scattered throughout all the heavens, and every particle has an innate gravity towards all the rest and the whole space throughout which this matter was scattered was but finite: the matter on the outside of this space would by its gravity tend towards all the matter on the inside and by consequence fall down to the middle of the whole space and there compose one great spherical mass. (Correspondence, 234)

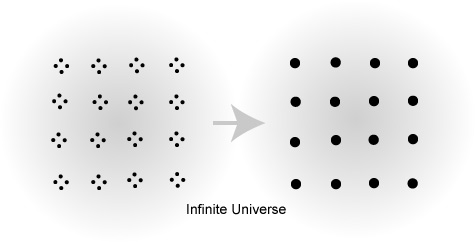

But if the matter was evenly diffused through an infinite space, it would never convene into one mass but some of it convene into one mass and some into another so as to make an infinite number of great masses scattered at great distances from one to another throughout all the infinite space. (Correspondence, 234)

But how the matter should divide itself into two sorts and that part of which is fit to compose a shining body should fall down into one mass and make a Sun and the rest which is fit to compose an opaque body should coalesce not into one great body like the shining matter but into many little ones: or if the Sun was at first an opaque body like the planets, or the Planets lurid bodies like the Sun, how he alone should be changed into a shining body whilst he remains unchanged, I do not think explicable by mere natural causes but am forced to ascribe it to the counsel and contrivance of a voluntary Agent. ... Why there is one body in our System qualified to give light and heat to all the rest I know no reason but because the author of the System thought it convenient, and why there is but one body of this kind I know no reason but because one was suffricient to warm and enlighten all the rest. (Correspondence, 234)

To your second Querry I answer that the motions which the Planets now have could not spring from any natural cause alone but were impressed by an intelligent Agent. ... it's plain that there is no natural cause which could determine all the Planets both primary and secondary to move the same way and in the same plane without any considerable variation. This must have been the effect of Counsel. Nor is there any natural cause which could give the Planets those just degrees of velocity in proportion to their distances from the Sun and other central bodies about which they move and to the quantity of matter contained in those bodies, which were requisite to make them move in concentric orbs about those bodies. (Correspondence, 234-5)

* * * * *

The reason why matter evenly scattered through a finite space would convene in the midst you conceive the same with me: but that there should be a Central particle so accurately placed in the middle as to be always equally attracted on all sides and thereby continue without motion, seems to me a supposition fully as hard as to make the sharpest needle stand upright on its point upon a looking glass. For if the very mathematical center of the central particle be not accurately in the very mathematical center of the attractive power of the whole mass, the particle will not be attracted equally on all sides.

And much harder it is to suppose that all the particles in an infinite space should be so accurately posed one among another as to stand still in a perfect equilibrium. For I reccon this as hard as to make not one needle only but an infinite number of them (so many as there are particles in an infinite space) stand accurately poised upon their points. Yet I grant it possible, at least by a divine power; and if they were once so placed I agree with you that they would continue in that posture without motion for ever, unless put into new motion by the same power. When therefore I said that matter evenly spread through all spaces would convene by its gravity into one or more great masses, I understand it of matter not resting in an accurate poise. (Correspondence, 238)

But notice that the reasoning in the last quotation applies to the right-hand side of the figure for the infinite universe. This means that we need a "fine tuning" for the initial condition of the infinite universe. Similar problems arise even for the contemporary cosmology, although the background theory is not the Newtonian mechanics but the general relativity and the quantum mechanics.

References

The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, Vol. III (1688-1694), ed. by H. W. Turnbull, Cambridge University Press, 1961.

ハリソン、E. (2004) 『夜空はなぜ暗い?』(長沢工監訳)地人書館(原著1987)

Last modified, June 17, 2005. (c) Soshichi Uchii