Bohr Meets EPR

Bohr's Reply to Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen

Bohr's reply to EPR appeared in the next issue of the Physical Review (48, 696-702 [1935]). This reply is longer than the opponents' paper, and Bohr seems to have endeavored to give a definitive and decisive blow to Einstein and others.

At the outset, Bohr quotes their “criterion of reality”, and against this, Bohr asserts: ”a criterion of reality like that proposed by the named authors contains … an essential ambiguity when it is applied to the actual problems with which we are here concerned.” But Bohr does not immediately show this. Instead, he begins with much simpler examples of measuring arrangements, in order to make clear the peculiarity of the measurements in quantum mechanics. Without due regard to this peculiarity, any criterion of reality is bound to fail---so suggesting Bohr.

First, suppose a particle is passing through a diaphragm with a slit. According to the quantum mechanics, Heisenberg's indeterminacy principle holds, and this tells us that if we want to determine the momentum p of the particle after it has passed the slit, its indeterminacy (with respect to momentum) is greater the narrower the slit. Since the width of the slit determines the indeterminacy of the position q of the particle, the product of these two kinds of indeterminacy cannot be smaller than a certain amount, determined by Planck's constant h . Then we have a choice. We can arrange to measure the momentum, or the position, of the particle by setting a suitable experimental device. But whichever arrangement we choose, this choice excludes the other alternative---this is Bohr's point. For, any such experimental device and the the result of such an experiment must be described in terms of unambiguous classical terms; otherwise we cannot apply the concepts of momentum or position .

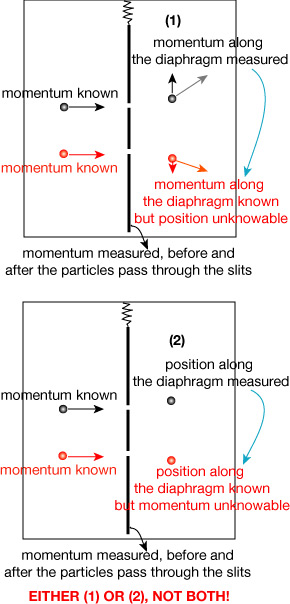

Then, Bohr comes closer to EPR experiment, presenting the following 2-slit experiment: With this arrangement, you still have a free choice whether to measure the momentum or to measure the position of the first particle, BUT NOT BOTH!

With this preparation, Bohr now turns to EPR argument. Bohr points out: “the wording of the above-mentioned criterion of physical reality … contains an ambiguity as regards the meaning of the expression ‘without in any way disturbing a system'.” Of course, when a measurement is made in the EPR experiment, there is no question of a mechanical disturbance of the system (the far-way particle). However, Bohr continues:

But even at this stage there is essentially the question of an influence on the very conditions which define the possible predictions regarding the future behavior of the system . Since these conditions constitute an inherent element of the description of any phenomenon to which the term “physical reality” can be properly attached, we see that the argumentation of the mentioned authors does not justify their conclusion that quantum-mechanical description is essentially incomplete.

Although Bohr's paper still continues, I believe the preceding contains the essential part of Bohr's reply. In Bohr's 1949 paper, Bohr seems to be saying that the preceding answer is still not clear enough, and Bohr in fact elaborates the same point with many other examples and figures.

Finally, we should mention Einstein's response to Bohr's reply (after more exchanges in the post-war period). In Einstein's reply to criticisms in the 1949 volume, Einstein writes as follows:

Of the “orthodox” quantum theoreticians whose position I know, Niels Bohr's seems to me to come nearest to doing justice to the problem. Translated into my own way of putting it, he argues as follows:

If the partial systems A and B form a total system which is described by its ψ -function ψ /( AB ), there is no reason why any mutually independent existence (state of reality) should be ascribed to the partial systems A and B viewed separately, not even if the partial systems are spatially separated from each other at the particular time under consideration. The assertion that, in this latter case, the real situation of B could not be (directly) influenced by any measurement taken on A is, therefore, within the framework of quantum theory, unfounded and (as the paradox shows) unacceptable.

By this way of looking at the matter it becomes evident that the paradox forces us to relinquish one of the following two assertions:

(1) the description by means of the ψ -function is complete

(2) the real states of spatially separated objects are independent of each other. (Schilpp 1949, 681-2)

Eventually, Bohr and Einstein never convinced each other.

References

Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen "Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be Considered Complete?", in Wheeler and Zurek 1983.

Bohr, "Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be Considered Complete?", Physical Review 48 (1935), 696-702 [reprinted in Niels Bohr Collected Works, vol. 7]. The reprint version in Wheeler and Zurek 1983 lacks some portion. Japanese tr. in 『因果性と相補性』(山本義隆訳)、岩波文庫。

Bohr, "Discussion with Einstein on Epistemological Problems of Atomic Physics", in Schilpp 1949

Einstein, "Reply to Criticisms", in Schilpp 1949

Schilpp, P.A., ed. Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist , Tudor Publishing Co., 1949.

Wheeler and Zurek, ed. Quantum Theory and Measurement , Princeton, 1983.