"Space, Time, and Philosophy of Science---Newton, Leibniz, and the Present Theories"

Thanks to Prof. K. Ito and our students, I could deliver my final lecture for a number of people, many of whom came a long way from various cities in Japan, no, even from Los Angeles, USA! Here are some snapshots. For the snapshots of the party, go to the bottom of this page.

This instrument, recorder (sopranino) was quite popular when Leibniz was alive. The tune "stardust" comes from the 20th century. This combination was intentional; for I wished to say that the old controversy between Newton and Leibniz is still relevant to our contemporary problem of space and time, including cosmology. Their contrasting positions and views have been transformed in various ways by various people, but the basic features are still alive. So I played a newer tune by the old-fashioned instrument. We are still impressed by the stardust in the sky, aren't we?

Let's begin with the Leibniz-Clarke Correspondence, but we've got to examine Newton's own views of space and time, and of cosmology. Why did Leibniz criticized Newton and Newton's views? And what was Leibniz's own alternative view? All right, on Newton's view, even if we explain the origin of the material universe, the origin of space and time is still unexplained!

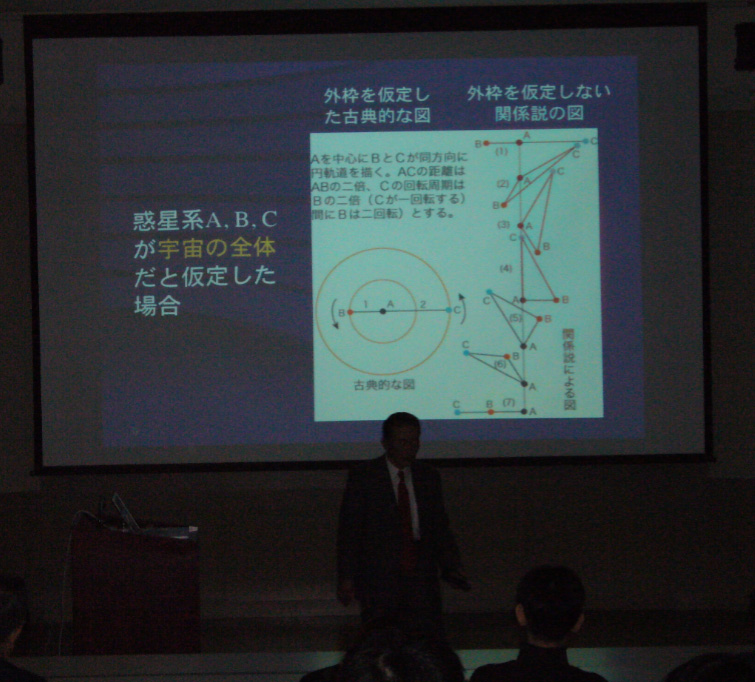

Leibniz propounded the relationalist view; and its ground is the principle of sufficient reason (including the principle of the identity of indiscernibles). What is the scenario of mechanics and cosmology on this view, and what is its merit? Since space and time are dependent on the matter in the universe, and the law of the whole universe produces space and time (in addition to the universe itself), Newton's difficulty disappears! The Leibnizian cosmology does not need any external frame, such as absolute space and time.

Of course, Leibniz's view had its weak points. How should we explain the centrifugal force arising from rotation (Newton's bucket)? How should we reproduce the law of inertia in the first place, on this view (Euler's criticism) ? Although the Leibnizian scenario was quite attractive, Leibniz did not have sufficient means for fulfilling it.

Anyway, the crux of the Newton-Leibniz antagonism is: how far should we demand the reason, in conformity with the principle of sufficient reason?

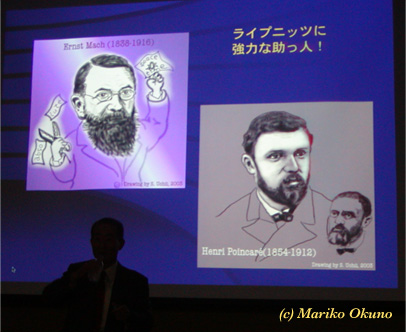

Now comes the two powerful supporters of the Leibnizian ideas: Mach and Poincare. Mach could dispense with the notion of force (which was central in Leibniz), without damaging the Leibnizian scenario of the relationalism. He also made an important suggestion for reconstructing the law of inertia. Poincare, on the other hand, clearly pointed out the problem of simultaneity and the duration, as well as the initial-value problem.

Also, Mach's suggestion of a huge bucket (Mach's bucket) had an important bearing on Einstein and general relativity.

There appeared several supporters of relationaslism in the 20th century, but they were ignored because of the fame of the two relativity theories by Einstein. The revival of the Leibnizian and the Machian ideas owes a great deal to Julian Barbour, a British independent physicist. He has shown that the Machian dynamics without external frame is possible, and the Newtonian mechanics can be reconstructed in this way.

Thus the Leibnizian idea of frameless dynamics became feasible. Not only that, Barbour has also shown that this appoach can be extended to the theory of gravity, general relativity. The supporters of the "loop quantum gravity" have shown that the quantum theory of gravity can be constructed along this line. Lee Smolin, in particular, may be regarded as a "disciple" of Barbour.

Of course, the loop quantum gravity is still short of unifying physics, because its scope is restricted within gravitation. Another, much more powerful theory, the super-string theory is now fashionable; this aims at a theory of everything, all of the four kinds of force in nature. But let us notice that the loop quantum gravity is a theory without external frame, whereas the super-string theory depends on the 10-dimensional external frame. Here, we can see the same sort of contrast as the one between Leibniz and Newton. The antagonism between them is not just an old-fashioned histrorical episode; it is still a live issue in the contemporary physics.

Let me add a final remark (not included in the lecture). I know several people are ciritizing me by saying that I praise Leibniz too much. But beware, you fools, Leibniz (and Newton, for that matter) is 100 times cleverer than you and me. We've got to be fair to a historical figure, and "to be fair" means in this context, not to repeat what Leibniz said in his old terms, but to make him alive in our contemporary situations (I am sick of a multitude of papers in which Leibniz is dead). Some of his doctrines may be indeed old-fashioned and wrong; but this does not invalidate many of his ideas (such ideas can be revitalized with enough of Leibniz' original context). Some of my former students said after the lecture, in his shabby blog, that my interpretation of Leibniz is a kind of Whiggism (i.e. the history which takes in the old items from the winner's point of view). I vehemently refuse the derogatory implication of this word. And I wonder why he can say this, because he does not seem to know much about Leibniz, except for such stereotypes as "monads", "teleology", and "preestablished harmony". Do you know Leibniz as he actually was? Isn't that a myth, to suppose the true history? And if you do not know the true history, there should be various ways to reconstruct history. I am just trying one of such ways.You see, the Leibnizian (and the Machian) dynamics has never become an "establishment" (winner) , but we still can find many jewels in it; I am trying to polish some of them (not by Whiggism but by the principle of charity). As long as we aim at philosophy of science, we've got to make a value judgment as regards science (what science should be). According to such a judgment, I am trying to reconstruct what Leibniz was trying to get at. I believe this attempt is much more worthwhile than a shabby criticism (only words, stereotypes) by a guy who just shies away from the hard core science, physics in particular. Wake up, you xxxxxx xxxx!

[3 photos by courtesy of Mariko Okuno, and the rest by anonymous students of our Lab.]

After the lecture, Prof. K. Ito and our students were good enough to celebrate my retirement, and a number of friends and former students joined. Here is the set of snapshots of the party. You can download any item from my site at .Mac. Also, you can download my performance of "Stardust" from the same site; go to the page of "Stardust" (heavy, 24MB! The file can be played , e.g. by Quicktime). I wish to thank my students for making the CD of my performance (not my best, but the actual performance, anyway).

Last modified May 8, 2006. (c) Soshichi Uchii

webmaster